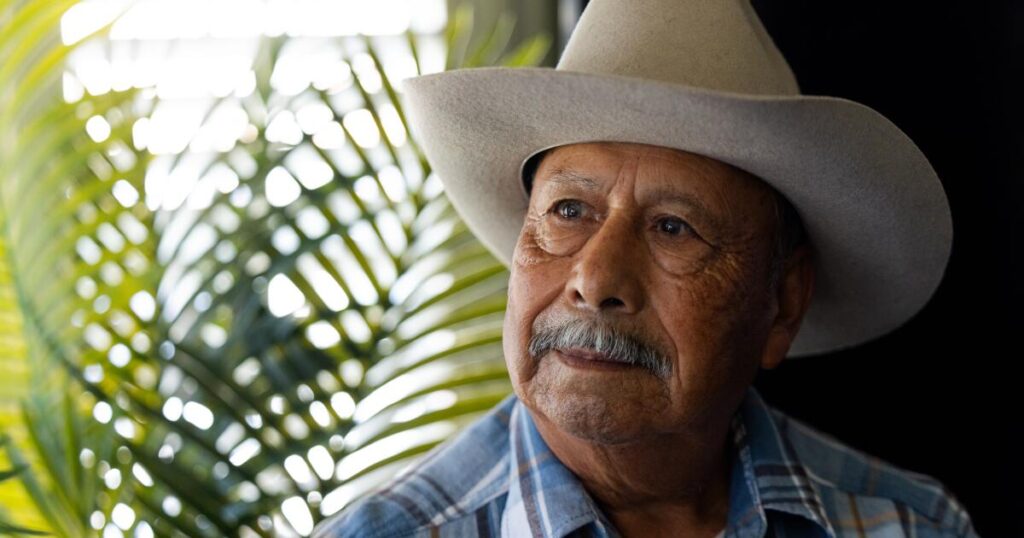

UPDATE: Former bracero Manuel Alvarado has voiced urgent concerns against the revival of the Bracero Program, warning that it could lead to the exploitation of workers. Speaking from his home in Anaheim, California, Alvarado stated, “If that happens, those people will be treated like slaves,” reflecting on his own painful experiences as a seasonal agricultural worker in the early 1960s.

In a critical moment for agricultural labor in the U.S., Alvarado’s testimony resonates as farmers plead with President Donald Trump to address labor shortages caused by ongoing deportations. “We can’t let our farmers not have anybody,” Trump noted in a recent interview, acknowledging that current policies are affecting crop yields.

The Bracero Program, which allowed over 2 million Mexican men to work legally in the U.S. between 1942 and 1964, is being reconsidered by lawmakers like Texas Rep. Monica De La Cruz. She argues that the original program “created new opportunities for millions,” but Alvarado vehemently disagrees based on his past.

Alvarado, now 85, recounted his journey from his family’s rancho in La Cañada, Zacatecas, to the U.S. when he was just 21. He described the harsh conditions faced by braceros, including humiliating medical inspections and meager wages—earning only 45 cents an hour in Colorado.

He emphasized that the revival of such programs would not benefit workers today, stating, “The people who’ll come will have no rights other than to come and get kicked out at the will of the government.” Alvarado highlighted the historical exploitation faced by braceros, especially at the hands of Mexican foremen in California.

Reflecting on the grueling hours of work—often 14 hours a day, seven days a week—Alvarado expressed disdain for the treatment he and his fellow workers endured. “They’d yell all the time — ‘¡Dóblense [Get to it], wetbacks!’” he recalled, illustrating the harsh realities of farm labor at that time.

His story sheds light on broader implications for agricultural policy as farmers face labor shortages amid strict immigration enforcement. As Trump considers reforms to address these challenges, many are left questioning the morality and feasibility of returning to a system that historically exploited vulnerable populations.

Alvarado’s experiences are not just historical anecdotes; they are a warning for the future. He urges lawmakers to recognize that many workers are already here, contributing to the economy, and that deportation only exacerbates labor shortages and human suffering. “Deporting them is horrible,” he stated firmly.

As the debate over agricultural labor continues, Alvarado’s voice serves as a critical reminder of the past injustices faced by braceros and the potential consequences of repeating history. His message is clear: any revival of the Bracero Program must prioritize workers’ rights and dignity.

With the situation developing rapidly, observers will be watching how policymakers respond to these pressing concerns in the coming weeks. Alvarado’s poignant reflections challenge the narrative surrounding immigration and labor, urging a more humane approach to a complex issue that affects millions.