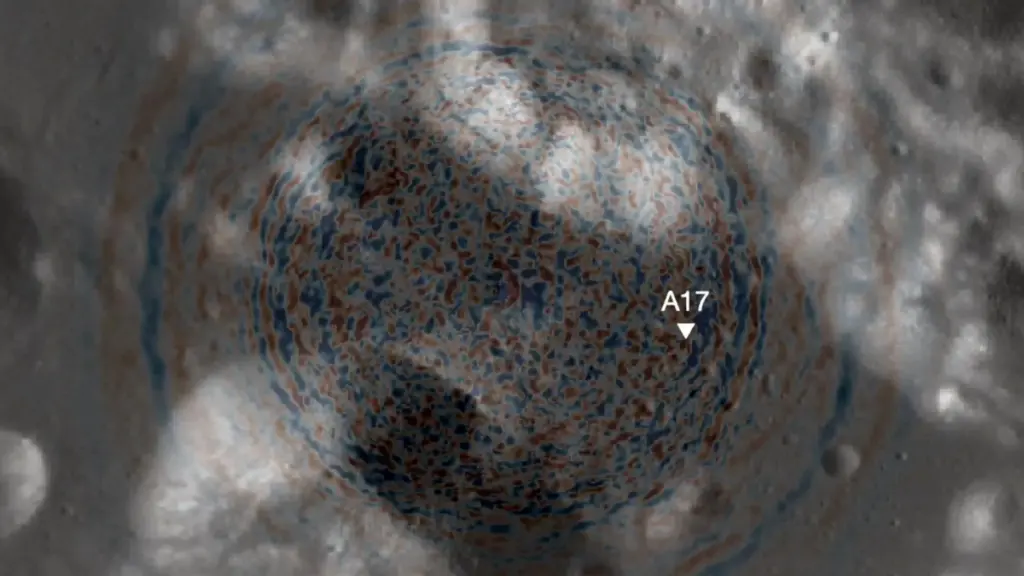

Recent research has revealed that moonquakes, rather than meteoroid impacts, are the primary cause of shifting terrain near the Apollo 17 landing site. This discovery could significantly influence NASA’s plans for future lunar missions and long-term habitats on the Moon.

Insights from Apollo 17 Data

The study, published in the journal Science Advances, was conducted by Thomas R. Watters, Senior Scientist Emeritus at the Smithsonian Institution, and Nicholas Schmerr, Associate Professor of Geology at the University of Maryland. Their research focused on the Taurus-Littrow valley, the landing site of the Apollo 17 mission in 1972. By analyzing geological samples and observations made by the Apollo astronauts, the team identified that the region’s shifting terrain primarily resulted from ancient moonquakes.

During the Apollo mission, astronauts documented boulder tracks and landslides believed to have been triggered by seismic activity. Watters and Schmerr used this evidence to estimate the strength of these past moonquakes and pinpoint the faults responsible for them. “We had to look for other ways to evaluate how much ground motion there may have been, like boulder falls and landslides that get mobilized by these seismic events,” Schmerr explained.

The Implications for Future Missions

The study indicates that moonquakes with magnitudes near 3.0—a level considered mild by Earth standards—have repeatedly shaken the Taurus-Littrow valley over the past 90 million years. These quakes are associated with the Lee-Lincoln fault, a tectonic feature running through the valley floor. The findings suggest that this fault, along with other young thrust faults on the Moon, might still be active, raising concerns about future lunar infrastructure.

“The global distribution of young thrust faults like the Lee-Lincoln fault should be considered when planning the location and assessing the stability of permanent outposts on the Moon,” Watters noted. Their research also calculated the statistical likelihood of damaging quakes, estimating a one in 20 million chance of such an event occurring on any given day. While this risk seems low, Schmerr emphasized that it cannot be ignored when planning long-term lunar missions.

Short-duration missions, like Apollo 17, face minimal risk due to their limited time on the lunar surface. However, projects involving longer stays, particularly those under the upcoming Artemis program, may encounter increasing risks. For instance, new lander designs, such as the Starship Human Landing System, could be more vulnerable to ground acceleration induced by moonquakes near active faults.

Schmerr elaborated, “If astronauts are there for a day, they’d just have very bad luck if there was a damaging event. But if you have a habitat or crewed mission up on the Moon for a whole decade, that’s a different story.” He likened the risk of a hazardous moonquake over an extended mission to going from “the extremely low odds of winning a lottery to much higher odds of being dealt a four of a kind poker hand.”

Advancing Lunar Seismology

This research contributes to the emerging field of lunar paleoseismology, which studies ancient seismic activity on the Moon. Unlike Earth, where scientists can excavate trenches to uncover evidence of past earthquakes, lunar researchers rely on existing data and orbital imaging. Schmerr anticipates significant advancements due to improved mapping technology and future Artemis missions, which plan to deploy more sophisticated seismometers than those used during the Apollo missions.

In summary, the researchers urge that future lunar exploration must take these seismic hazards into account. “Don’t build right on top of a scarp, or recently active fault. The farther away from a scarp, the lesser the hazard,” Schmerr advised.

This study was made possible with support from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter mission, which launched on June 18, 2009. The LRO, operated by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, provides critical data that enhances our understanding of the Moon’s geological activity. While the findings shed light on potential risks, they also pave the way for safer and more informed planning of human activities on the lunar surface.