The discovery of dogs with unusual blue fur in the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone has garnered significant attention, leading to a deeper understanding of the animal populations in this unique environment. The Chornobyl Nuclear Plant, site of the catastrophic disaster in 1986, is now home to thousands of animals, including approximately 900 stray dogs descended from pets abandoned during the evacuation. A recent sighting of three dogs with blue coats has sparked speculation about the effects of radiation or genetic mutations, but experts have offered alternative explanations.

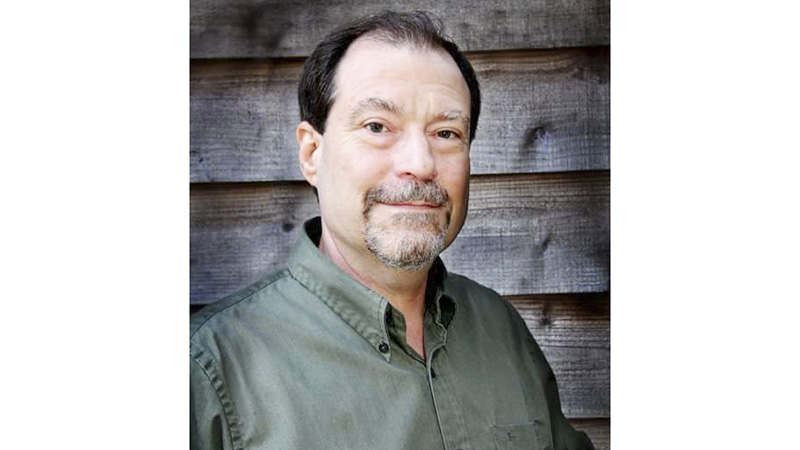

According to the Clean Futures Fund, which has been active in the region since 2017 through its Dogs of Chornobyl Program, the blue coloration likely resulted from the dogs rolling in waste from a tipped-over portable toilet. Timothy A. Mousseau, a biologist at the University of South Carolina and Scientific Advisor for the program, explained that the dogs’ fur absorbed blue-tinted contaminants, not radiation. Subsequent veterinary examinations indicated no signs of illness or genetic damage related to radiation exposure.

Research Uncovers Genetic Distinctions

The blue dogs have captured public imagination, but they are part of a broader narrative revealing the genetic uniqueness of Chornobyl’s dog populations. Mousseau and his team conducted research on 302 dogs from three free-roaming groups within the Exclusion Zone, including areas around the abandoned city of Pripyat, located about 16 km (10 miles) from the reactor. Their findings show that these dogs are genetically distinct from domestic populations elsewhere in Ukraine and Europe.

The study highlighted significant differences in the dogs’ genetic structure, particularly in their shared ancestral genome segments. The researchers identified 15 distinct family groups, some spanning multiple locations within the Exclusion Zone, indicating that the dogs migrate between different areas to find mates. This movement has helped maintain genetic diversity despite the overall isolation of the population.

Interestingly, genetic analysis revealed that dogs around the nuclear plant have a higher prevalence of shepherd-type DNA—approximately 9% of their chromosomes trace back to shepherd breeds. This genetic marker is likely linked to the historical use of German Shepherds and East-European Shepherds as guard dogs during the Soviet era. In contrast, the city populations exhibited a lower frequency of these markers, suggesting different breeding histories.

Environmental Impact and Wildlife Resilience

The research team also noted that while the dogs in the power-plant zone exhibited increased genetic similarity within their groups, no evidence indicated that they had developed increased resistance to radiation exposure. Mousseau emphasized that any differences in genetic makeup are primarily due to isolation rather than adaptive evolution.

Moreover, the Exclusion Zone has become a sanctuary for various wildlife species, including wolves, lynx, and even the endangered Przewalski’s horse. Previous studies on small mammals in the region, such as bank voles and wood mice, found no correlation between radiation levels and population sizes. The absence of human interference has likely allowed these populations to thrive, despite the potential biological damage from radiation.

Ongoing research continues to explore the long-term effects of radiation on the area’s fauna. While there have been instances of observable negative health outcomes, such as the rise of cataracts in birds, Mousseau pointed out that many studies show significant resilience among mammals, particularly in areas with lower radiation levels.

The Chornobyl Exclusion Zone spans over 2,600 km² (1,000 miles²), but only about 30% of the area is considered significantly radioactive. This variability creates a mosaic of radiation levels, which affects wildlife differently across the region.

As research evolves, the Chornobyl dogs remain a visible symbol of survival and adaptability in an environment once deemed uninhabitable. Mousseau noted that contrary to some media reports, these dogs show no signs of elevated cancer rates. Most cancers occur in older dogs, and the harsh conditions in Chornobyl limit their lifespan, further complicating the assessment of health impacts.

The story of Chornobyl’s blue dogs exemplifies the intricate relationship between wildlife and the environment, challenging previously held beliefs about radiation’s impact on life. Ongoing studies will continue to shed light on the resilience of the region’s animal populations and the complexities of their genetic makeup in the shadow of a historical disaster.