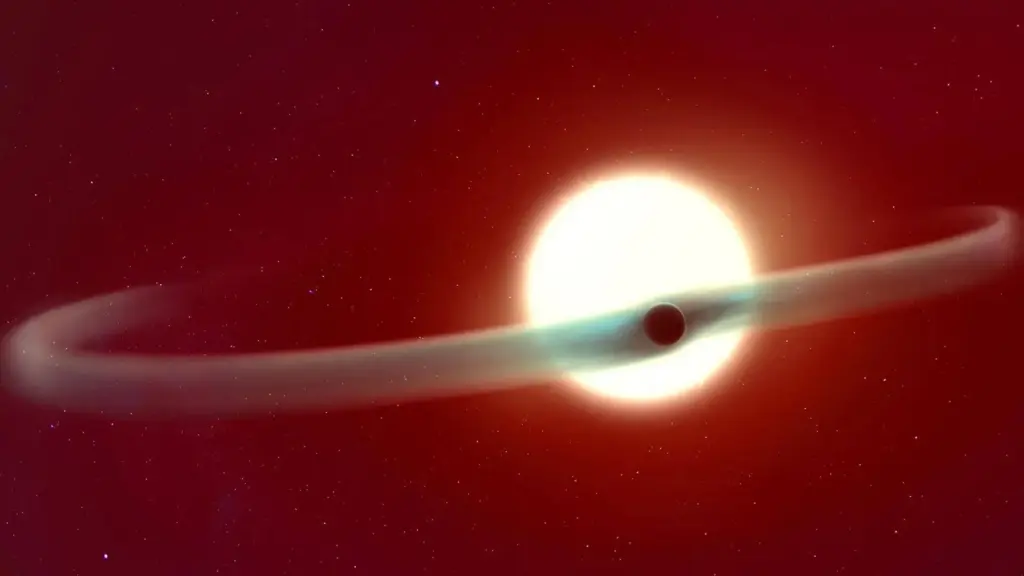

A team of astronomers has achieved a significant milestone in exoplanet research by continuously observing the gas giant WASP-121b losing its atmosphere. Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the researchers captured this phenomenon over a complete orbit, revealing stunning details about the planet’s atmospheric escape.

WASP-121b is classified as an ultra-hot Jupiter, a category that includes massive gas giants that orbit very close to their stars. The observations, which took place over nearly 37 hours, showed that the planet is not just losing gas through a single stream; instead, it is enveloped by two enormous helium tails. One tail trails behind the planet, reminiscent of a comet, while the other extends forward towards its star.

Breakthrough Observations

This groundbreaking study was conducted by astronomers from the Université de Genève (UNIGE), the National Centre of Competence in Research PlanetS, and the Trottier Institute for Research on Exoplanets (IREx) at the University of Montreal (UdeM). Their findings, published in Nature Communications, provide the most comprehensive view of atmospheric escape observed to date.

The intense radiation from the star heats WASP-121b’s atmosphere to temperatures exceeding several thousand degrees Celsius. Under these extreme conditions, lightweight elements like hydrogen and helium can easily escape into space. Over millions of years, this gradual atmospheric loss could drastically alter the planet’s size and composition.

Prior to this study, astronomers had only been able to observe atmospheric escape during brief planetary transits—when a planet passes directly in front of its star. These short observations, lasting only a few hours, provided limited insights. The continuous monitoring made possible by the JWST allowed researchers to track the structure and extent of escaping gases with unprecedented detail.

Discoveries and Implications

The research team employed the Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRISS) aboard the JWST to measure how helium absorbs infrared light, revealing that the gas extends well beyond the planet itself. The helium signal was detected for more than half of WASP-121b’s orbit, marking a new record for continuous observation of atmospheric escape.

One of the most surprising aspects of the findings was the discovery of the two distinct helium tails, which stretch across a distance greater than 100 times the planet’s diameter. This is more than three times the distance between WASP-121b and its star. According to Romain Allart, the lead author of the study and a postdoctoral researcher at UdeM, “We were incredibly surprised to see how long the helium escape lasted. This discovery reveals the complexity of the physical processes that sculpt exoplanetary atmospheres and their interaction with their stellar environment.”

Despite advances in understanding atmospheric escape, current numerical models developed at UNIGE struggle to replicate the double-tailed structure observed around WASP-121b. Co-author and doctoral student Yann Carteret emphasized that this discovery highlights the need for new three-dimensional simulations to analyze the physics governing these processes.

The successful detection of helium in such detail opens new avenues for future research. Scientists aim to determine whether the twin-tail structure observed around WASP-121b is unique or a common feature among hot exoplanets. As the JWST continues to provide sensitive measurements, researchers will refine their theoretical models to better explain the interactions between gravity, radiation, and stellar winds that shape escaping atmospheres.

Vincent Bourrier, a lecturer and researcher in the Department of Astronomy at UNIGE, concluded, “Very often, new observations reveal the limitations of our numerical models and push us to explore new physical mechanisms to further our understanding of these distant worlds.”

This study represents a significant leap in exoplanet research, showcasing the capabilities of the JWST and paving the way for future discoveries regarding the atmospheres of distant planets.