In a recent reflection on the state of journalism, Chris Quinn highlights an essential truth: the danger of forgetting valuable practices. Quinn draws parallels between the evolution of journalism and traditional painting techniques, emphasizing the importance of both in understanding our history and improving our future.

Quinn notes that the human journey is marked by a quest for enlightenment, characterized by progress and regression. He recalls a quote from the 1981 film Excalibur: “It is the doom of men that they forget.” This notion resonates deeply within the context of journalism, where crucial skills and relationships often fade with the shift towards digital reporting.

As a woodworker, Quinn has experienced firsthand the transition from basic enamel paints to more enduring options like milk paint. He explains that while milk paint was once common, it fell out of favor as newer materials emerged. The resurgence of interest in milk paint, sparked by figures like Nick Kroll and Chris Schwarz, underscores how easily valuable knowledge can be lost. Kroll’s book on creating milk paint at home has provided woodworkers with a simple and effective alternative that yields impressive results.

Similarly, Quinn shares his struggles with outdoor paints that failed to withstand the elements. After numerous attempts using various modern products, he turned to linseed oil paint, a traditional European choice that has proven to be remarkably durable. This paint not only breathes but also ages gracefully, maintaining its integrity far longer than contemporary options. He notes that linseed oil paint was the standard before World War II, but has now become largely forgotten.

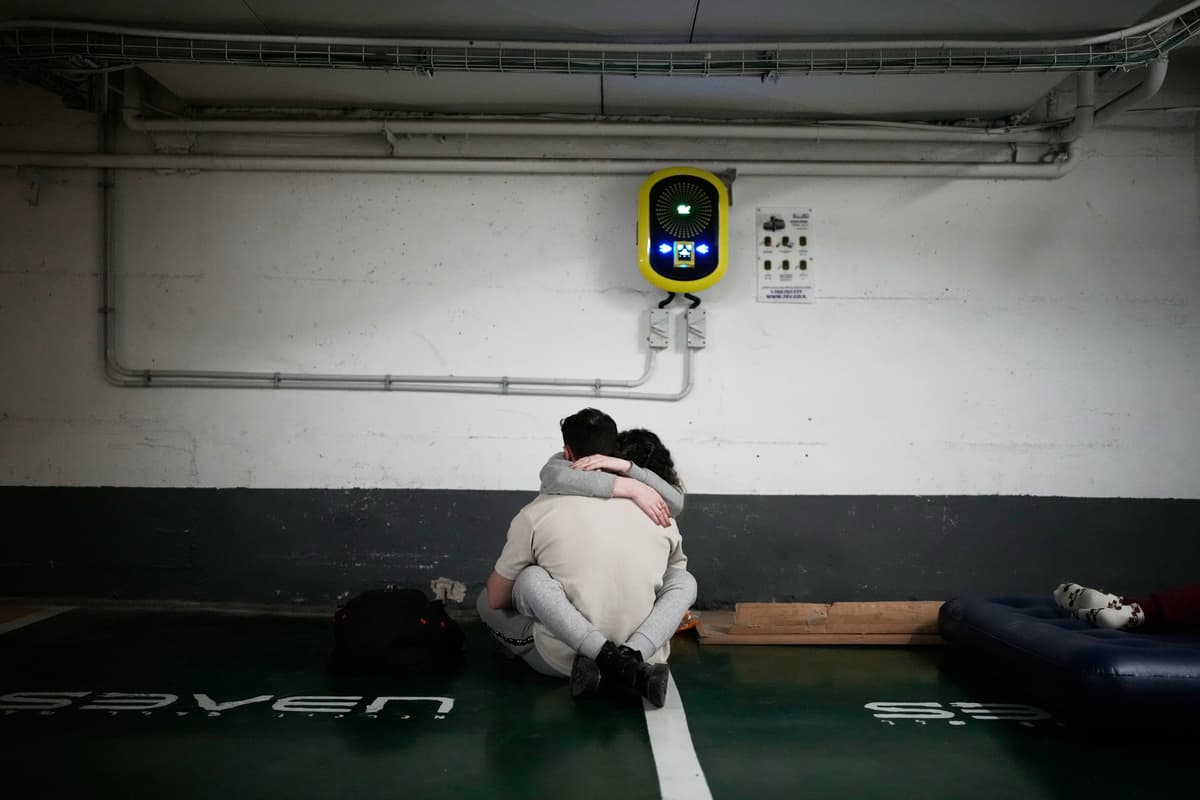

Transitioning to journalism, Quinn reflects on his years as a reporter, where informal conversations were a primary source of news. These interactions often provided insights that formal meetings and documents could not. The shift to digital journalism has diminished these valuable exchanges due to economic pressures, leading to fewer reporters and a higher demand for content.

The reduction in resources has forced reporters to produce more stories, take their own photographs, and manage numerous other tasks, diminishing opportunities for the kind of informal discussions that can yield compelling stories. Quinn stresses the need to reclaim this practice, not only for the benefit of the stories but also for the well-being of journalists themselves.

He expresses optimism about the role of artificial intelligence in journalism, which may offer solutions to the challenges faced by reporters today. By integrating AI into workflows for tasks such as copy-editing and headline writing, journalists could free up significant time to engage in meaningful interactions with their communities. While the demand for content remains unchanged, AI represents a potential turning point that could enhance the quality of journalism.

Quinn encourages a renewed focus on community engagement and the relationships that underpin effective reporting. By prioritizing these interactions, journalists can enrich their storytelling and foster a deeper connection with their audiences. Ultimately, he hopes that this approach will lead to happier reporters and a more informed public.

In conclusion, the lessons drawn from both the world of woodworking and journalism highlight a critical need to remember and revive traditional practices. As society continues to evolve, maintaining a connection to the past—whether through paint or storytelling—will be vital for future progress.