The recent investigation into loneliness in China uncovers deep cultural nuances regarding connection and belonging. Conducted by the Annecy Behavioral Science Lab in collaboration with the Global Initiative on Loneliness and Connection, this study involved interviews with 20 participants across various ages and regions. The findings challenge Western assumptions that loneliness is predominantly a relationship issue, illuminating how place and cultural practices shape emotional experiences.

Participants expressed that feelings of disconnection stem not only from missing individual people but also from a profound sense of loss tied to their hometowns and the rituals that reinforce belonging. One participant stated, “First of all, it is my hometown. I have been in my hometown for 19 years, so I have a very deep sense of connection to my hometown.” This highlights the significance of geographic roots in defining personal identity and community ties.

The study indicated that traditional social structures are under threat from rapid modernization and migration. As individuals leave their hometowns for work, they often lose the connections that form the bedrock of their social lives. In southeastern coastal regions, entire villages consist of interconnected clans sharing surnames and ancestry. These bonds are continuously reinforced through rituals such as ancestral worship and the Spring Festival, which emphasize the importance of geographic proximity and familial continuity.

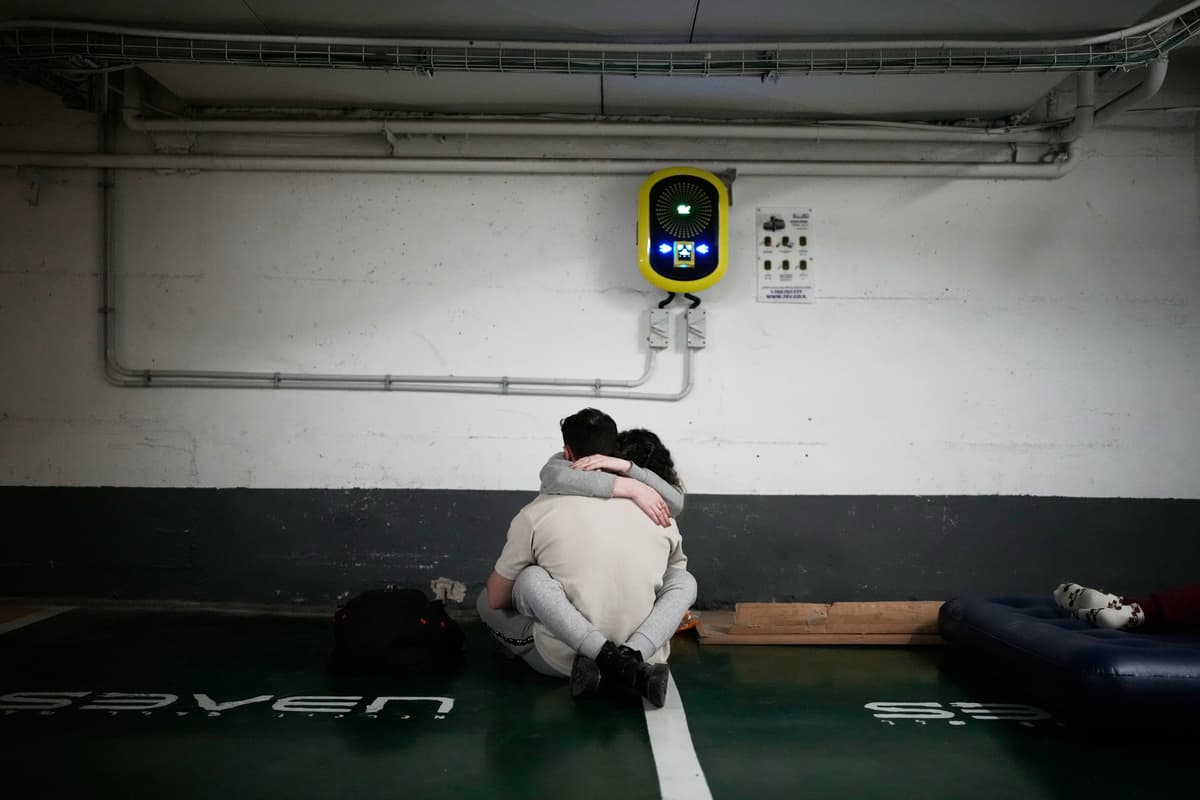

During festivals, many participants reported acute feelings of loneliness when unable to return home. One individual emphasized the necessity of returning to hometowns during significant holidays, stating, “In our country, even if the atmosphere in the original family is not good, people still need to return to their hometowns during specific holidays like the Spring Festival.” Missing these gatherings signifies a disconnection from the mechanisms that constitute belonging in Chinese culture.

Moreover, loneliness in China is often experienced silently. Participants noted a cultural reluctance to openly discuss feelings of loneliness, associating such admissions with personal failure. One participant explained, “Loneliness is quite abstract, and people often don’t know how to describe it in words.” This stigma creates a vicious cycle where individuals feel isolated and unable to seek help, as loneliness itself hampers effective communication.

The psychological impacts of loneliness reported by participants included feelings of emotional absence, helplessness, and emptiness. Some described physical manifestations such as constant illness and disrupted sleep patterns. Yet, formal help-seeking remains infrequent, with only one participant expressing a desire to see a psychologist, citing financial constraints.

Participants also highlighted a paradox within China’s social landscape. Although there is an emphasis on social connection, many described their interactions as superficial. One participant noted, “In China, social connections are often superficial, with everyone wasting large amounts of time and energy on social connection performance, which in turn deepens people’s sense of loneliness.” This sentiment reflects a broader discontent with the performative nature of social interactions, where rituals do not necessarily translate into meaningful connections.

Additionally, the investigation revealed that connections can extend beyond human relationships. Participants often described strong bonds with pets and nature, indicating that emotional ties can be rooted in various forms of belonging. For some, a pet became a focal point of connection, prompting them to make special efforts to return home for their animal rather than for family. This highlights a broader understanding of connection that transcends traditional familial ties.

The implications of this research suggest that effective interventions addressing loneliness in China must consider its unique cultural frameworks. Measurement tools should incorporate dimensions of place-based belonging, as standard loneliness scales may overlook the geographic aspects central to the Chinese experience. Policies surrounding holidays and travel should also aim to facilitate access to events that reinforce belonging.

Understanding loneliness in China requires recognizing the disruption caused by modernization and migration on traditional social structures. The experience of a migrant worker missing the Spring Festival is not merely about family separation; it reflects a rupture in the essential connections to place and ritual that foster a sense of belonging.

This research was supported by the Templeton World Charity Foundation and led by Hans Rocha IJzerman and Miguel Silan. The China team included Xin Liu and several others, contributing to a nuanced understanding of loneliness that resonates deeply within China’s cultural context. The full report is accessible through the Annecy Behavioral Science Lab for those interested in exploring the findings further.