An innovative study from the University of Portsmouth in the U.K. has successfully visualized anxiety in the brain, offering a fresh perspective on how this widespread mental health condition manifests. This groundbreaking research aims to enhance understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of anxiety by mapping the brain’s biological response during “no-win” situations—circumstances where individuals must choose between two undesirable options.

Traditional studies have largely focused on “approach–avoid” conflict, which contrasts a positive outcome with a lesser option. In contrast, the Portsmouth team explored “avoid–avoid conflict,” which more accurately reflects real-life anxiety scenarios. According to neuropsychologist Benjamin Stocker, this research marks the first instance of observing complex, anxiety-related decision-making in real-time within the brain.

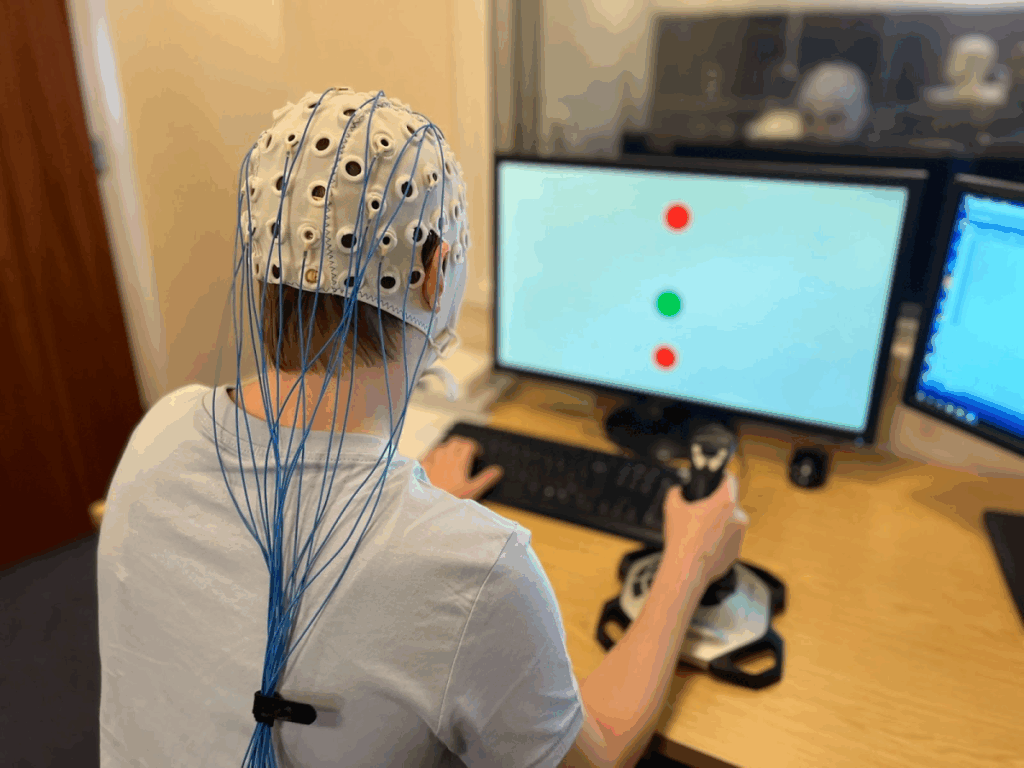

The study involved 40 young adults aged 18 to 24 who participated in a video-game-like task, where they used a joystick to navigate away from threatening objects on a screen. The difficulty of the task varied, with some scenarios being straightforward (low conflict) while others forced participants to choose between two negative outcomes (high conflict). Researchers utilized electroencephalography (EEG) to measure brain activity during these tasks, integrating it with the “avoid–avoid” conflict for the first time.

EEG is a non-invasive technique that effectively records electrical activity in the brain. The findings revealed distinct patterns of brain activity during “no-win” situations, particularly in the right frontal area, where increased levels of theta waves were observed. Other brain regions also demonstrated varying levels of activity based on the stressfulness of the situation. The researchers suggest these patterns may serve as a potential signature for anxiety-related conflicts.

“Anxiety shows up in many different ways in the brain,” Stocker stated. “Our methods allow us to not only show what brain regions are working during the processing of anxiety but also how these regions are communicating.”

The results of the study were robust, indicating a significant difference in brain activity between high-conflict and low-conflict scenarios. This could have profound implications for diagnosing and treating anxiety. Currently, diagnosis often relies on subjective assessments and trial-and-error methods with medications, which may not work effectively for everyone. Understanding how the brain reacts in high-stress situations could lead to identifying patterns that complicate decision-making processes.

Stocker emphasizes that this research could pave the way for non-pharmaceutical interventions, such as brain-based training or targeted psychological therapies. These approaches would directly address the anxiety patterns identified in the study, potentially enabling individuals to recognize when they are caught in an anxious cycle and to retrain their responses before they become overwhelming.

While acknowledging the limitations of the study, including individual differences in brain responses, Stocker believes this research is a step toward more objective methods of identifying anxiety. He notes that these findings should complement clinical judgment rather than replace it, serving as an additional tool to validate clinicians’ observations.

Looking ahead, the research team plans to validate their findings against the effects of anxiety-reducing medications and to expand their studies to larger and more diverse groups. In the long term, established brain patterns might help identify individuals most likely to benefit from specific treatments or even serve as a monitoring tool to assess the effectiveness of therapies.

Stocker envisions a future where a portable EEG device could be utilized in mental health clinics or primary care settings to support diagnosis and treatment. “While that is still some way off, this research brings us a step closer to more personalized and precise approaches to understanding and managing anxiety,” he concluded.

The study was published on March 15, 2025, in the International Journal of Psychophysiology. For those interested in further developments in anxiety research, the findings signify a significant advancement in neuroscience and mental health treatment methodologies.