In 1925, two unlikely figures—a hatter named Joseph Edwin Barnard and a former railway station clerk, William Ewart Gye—made a groundbreaking contribution to cancer research. Their work was so significant that it was featured in The Lancet, a prestigious medical journal, which described their findings as “an event in the history of medicine.” These findings hinted at the existence of a cancer virus, a discovery that electrified the scientific community and sparked widespread public interest.

As the studies were set to be published, a crowd gathered outside The Lancet‘s office in London, driven by rumors of the cancer “germ” being observed for the first time. The atmosphere was charged with anticipation; what had previously been a complex and poorly understood disease was suddenly at the forefront of medical discourse. Cancer research had matured alongside advances in bacteriology over the previous decades, but the idea of a germ linked to cancer was a novel proposition that captured imaginations.

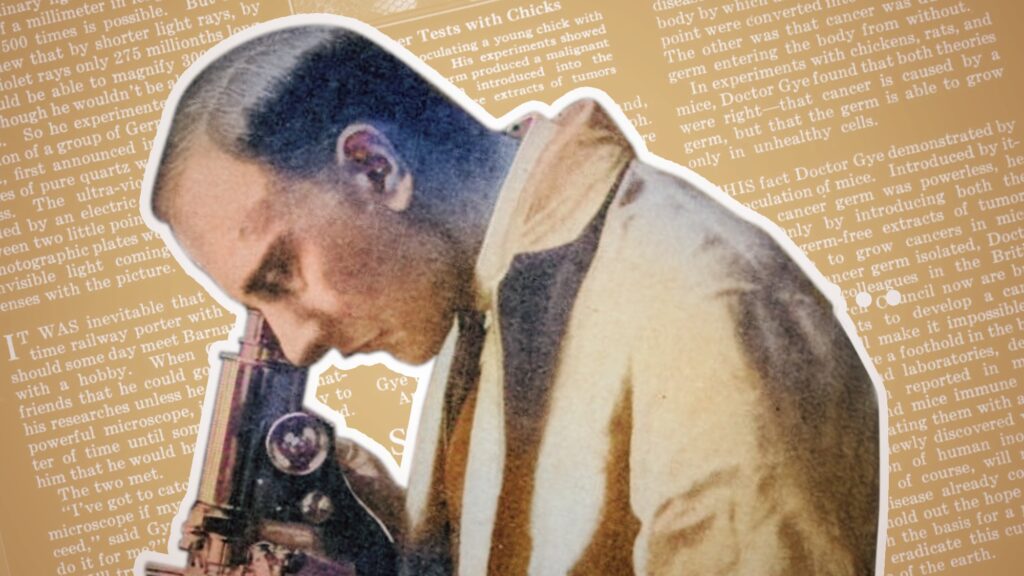

Joseph Edwin Barnard led a dual life—by day, he crafted fine hats at J. Barnard & Sons, a family business in London, while at night, he delved into his private laboratory. Barnard’s passion for microscopy drove him to develop innovative techniques using ultraviolet light and custom lenses, allowing him to view microorganisms with unprecedented clarity. His relentless curiosity and technical skills positioned him as a key figure in this scientific endeavor.

The story of William Ewart Gye is equally intriguing. Born in 1889 as William Ewart Bullock, Gye changed his surname in 1919, a decision shrouded in mystery. Some speculate it was to avoid confusion with a notable bacteriologist, while others suggest it was an homage to his suffragette wife, Elsa Gye. Gye’s unconventional path into medicine was marked by his dedication and an enigmatic reputation, further fueled by the circumstances surrounding his name change.

The Collaboration That Changed Cancer Research

When Gye and Barnard joined forces in London, they combined their expertise to push the boundaries of cancer research. Gye brought a deep understanding of experimental biology and germ theory, while Barnard offered exceptional microscopy skills. Together, they aimed to unravel the complexities of cancer, building upon the scientific advancements initiated by pioneers like Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur in the late 19th century.

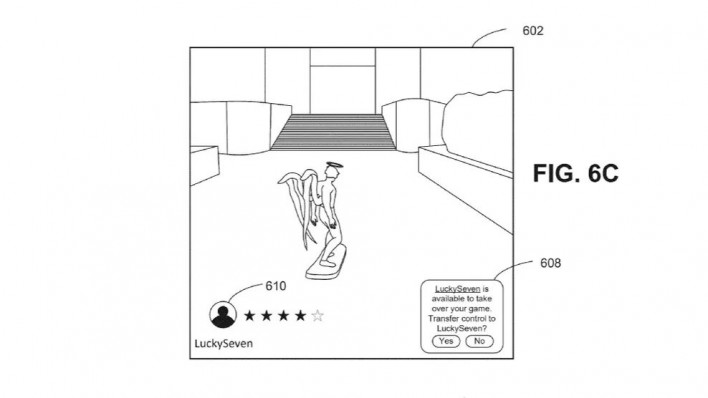

Their collaboration culminated in the discovery of what they termed “particulate bodies,” which they believed indicated the presence of a cancer virus. Barnard published photographs in The Lancet, illustrating distinct cellular structures with varying wall thicknesses. He hypothesized that these differences stemmed from viral replication within the cells. This breakthrough led to early hopes for a cancer vaccine that could prevent the disease from taking root.

In a significant development, Gye proposed a two-factor theory of cancer, suggesting that it resulted from the interaction between a virus and damaged cells. This was a departure from the prevailing belief that cancer arose solely from germs or environmental irritants. His meticulous experiments demonstrated that tumors could be induced in chickens only when both the cancer virus and tumor extract were present.

Lasting Impact on Cancer Research

While Gye‘s two-factor theory was not entirely accurate, it provided valuable insights that continue to inform cancer research today. A century later, the quest for a definitive solution to cancer remains ongoing. The editors of The Lancet were correct in asserting that this discovery marked a pivotal moment in medical history, laying the groundwork for modern molecular cancer research.

Current understanding recognizes cancer as a complex group of diseases driven by genetic mutations, environmental factors, and, in certain cases, viruses such as HPV and Epstein-Barr virus. Today’s researchers employ advanced technologies, including electron microscopes and super-resolution imaging, to explore cellular mechanisms and pathways that govern cell growth and death.

The optimism surrounding Barnard and Gye‘s work in 1925 has been tempered by a century of intricate discoveries. Nevertheless, significant strides have been made in cancer prevention, early detection, and treatment, transforming patient outcomes and offering hope for the future. Their groundbreaking work exemplifies how passion and determination can lead to monumental changes in scientific understanding, reminding us that innovation often comes from unexpected sources.