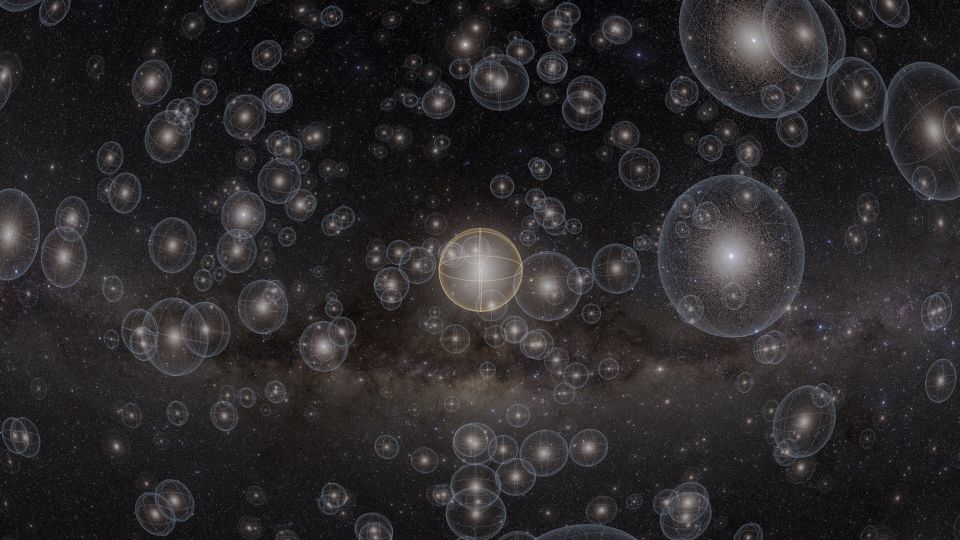

An unexpected discovery at the Hayden Planetarium in New York City may significantly alter our understanding of the Oort Cloud, one of the most enigmatic structures in our solar system. During the preproduction of a show titled “Encounters in the Milky Way,” a spiral formation was observed within the Oort Cloud, challenging the long-held belief that it is a spherical expanse of icy bodies.

The Oort Cloud, situated at a distance 1,000 times greater than Neptune’s orbit, has never been directly observed. Its existence was first proposed in 1950 by Dutch astronomer Jan Oort. Despite its elusive nature, the cloud is believed to be the solar system’s most distant region, composed of icy remnants from the solar system’s formation.

A Serendipitous Revelation

While testing a scene that depicted Earth’s celestial neighborhood, curators were surprised by the appearance of a spiral structure on the planetarium’s dome, reminiscent of a spiral galaxy. Jackie Faherty, an astrophysicist at the American Museum of Natural History and curator of the show, described the moment of discovery: “We hit play on the scene, and immediately we saw it. It was just there.”

To investigate further, Faherty consulted David Nesvorny, a scientist at the Southwest Research Institute and an Oort Cloud expert. Nesvorny had provided the scientific data for the scene and initially suspected an artifact in the visualization. However, upon reviewing his data, he confirmed the spiral’s presence and published his findings in The Astrophysical Journal.

The Galactic Tide and Its Implications

Nesvorny’s simulations, run on NASA’s Pleiades Supercomputer, revealed that the spiral is a result of the galactic tide—the gravitational influence of the Milky Way on the Oort Cloud’s icy bodies. This gravitational field twists the orbital planes of these bodies, creating the spiral formation.

“The spiral is in the inner part of the Oort Cloud, closest to us,” Nesvorny explained, noting that the outer portion likely remains spherical. The discovery highlights the dynamic nature of our solar system and its interaction with the broader galaxy.

“If you’re going to come up with a theory of how solar systems evolve, you should take into account the kind of shapes you might have in their structure,” said Faherty.

Challenges and Future Prospects

Despite the breakthrough, observing the Oort Cloud remains a challenge due to the small size and vast distance of its constituent bodies. The Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile, which recently became operational, may aid in discovering and observing these bodies, though it is unlikely to visualize the spiral in its entirety.

Experts like Malena Rice from Yale University see the finding as a pivotal moment in understanding our solar system’s place in the galaxy. “This result reshapes our mental image of our home solar system, while also providing a new sense for what extrasolar systems’ Oort clouds may look like,” she noted.

However, Edward Gomez from Cardiff University cautions that the findings are theoretical, based on simulations. “What they are proposing could be true, but it could also be modeled by other shapes of the Oort cloud or physical processes,” he said.

Looking Ahead

Confirming the spiral’s existence will require further observations and potentially new technology. Simon Portegies Zwart from Leiden University expressed skepticism about witnessing the spiral soon, though he remains hopeful that the Vera Rubin Observatory will uncover more Oort Cloud objects.

The discovery at the Hayden Planetarium underscores the power of visualization in scientific exploration and the potential for planetariums to serve as research tools. As Faherty remarked, “I truly believe that the planetarium, the dome itself, is a research tool. This is science that hasn’t had time to reach your textbook yet.”

While the spiral remains a theoretical construct for now, its implications for our understanding of the solar system and its evolution are profound, offering a glimpse into the complex gravitational interplay that shapes our cosmic neighborhood.