A recent study indicates that two groups of Neanderthals, residing in the Amud and Kebara caves in northern Israel, exhibited notable differences in their butchery techniques, despite their proximity and shared resources. This research suggests that these groups may have developed distinct local food traditions, highlighting the complexity of Neanderthal culture.

According to Anaëlle Jallon, a Ph.D. candidate at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and lead author of the study published in Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology, the variations in cut-mark patterns between the two sites could reflect unique traditions in how each group processed animal carcasses. “Even though Neanderthals at these two sites shared similar living conditions and faced comparable challenges, they seem to have developed distinct butchery strategies,” Jallon explained.

Both the Amud and Kebara caves are located only 70 kilometers apart and were occupied by Neanderthals during the winters between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago. Archaeological findings at both sites include burials, stone tools, hearths, and remnants of food. Evidence suggests that both groups relied on similar prey, primarily gazelles and fallow deer, yet their butchery practices differ significantly.

At the Kebara site, Neanderthals appear to have hunted larger prey more frequently and transported substantial kills back to the cave for butchering. In contrast, the Amud group left behind a higher percentage of burned and fragmented bones—about 40%—which could indicate cooking or accidental damage during processing. The Kebara site showed only 9% of burned bones, which were less fragmented and likely cooked.

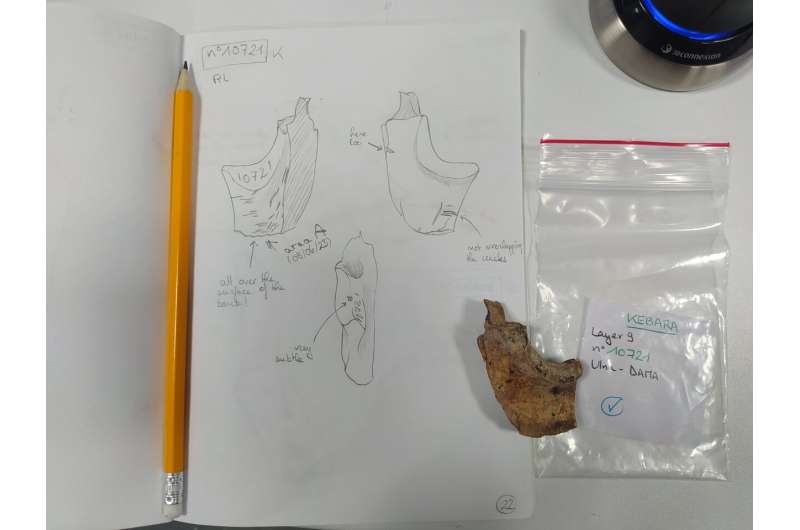

To investigate these differences, researchers analyzed a sample of cut-marked bones from both sites, examining the distinct characteristics of the cut marks. The cut marks at Amud were found to be more densely packed and less linear than those at Kebara. While similar patterns might suggest uniform butchery practices, the differences indicate varied cultural traditions.

The researchers considered various hypotheses to explain these findings. It is possible that the Neanderthals at Amud treated their meat differently prior to butchering, perhaps by drying or allowing it to decompose, similar to modern butchering practices. Such methods could make the meat more challenging to process, resulting in the observed differences in cut-mark formation.

Another potential factor could be the organization of the butchering process within each community. Variations in the number of individuals involved in butchering a kill may have influenced the distinct patterns observed.

Jallon acknowledged the limitations of the study, noting that some bone fragments were too small to provide a comprehensive understanding of butchery marks. While efforts were made to account for fragmentation biases, there remains a need for further research. “Future studies, including more experimental work and comparative analyses, will be crucial for addressing these uncertainties—and maybe one day reconstructing Neanderthals’ recipes,” she stated.

This research not only sheds light on Neanderthal subsistence strategies but also opens up questions about the social and cultural practices that influenced their food preparation methods. The findings underscore the complexity of Neanderthal life, revealing that even in their butchery techniques, local traditions and community practices likely played a significant role.