In a significant move for educational equity, Chicago established its first public school named after a Black individual in 1936. This milestone was marked by the opening of DuSable High School, dedicated to Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, who is recognized as the city’s first non-indigenous settler. Situated to serve an exclusively Black student population, DuSable represented a pivotal shift in the naming of public schools within the city.

Today, schools across Chicago celebrate the legacies of influential Black figures, such as Harold Washington Elementary School, named after the first Black mayor of Chicago, and Walter H. Dyett High School for the Arts, honoring a renowned musician. However, prior to the establishment of DuSable High School, most institutions were named after white men, reflecting a historical bias in the educational landscape.

The push to create DuSable High School stemmed from both a growing recognition of Du Sable’s importance and the pressing need for educational facilities catering to the Black community. According to Elizabeth Todd-Breland, an associate professor of history at the University of Illinois at Chicago, the early 20th century saw a surge in awareness regarding Du Sable’s contributions. His legacy as an entrepreneur and trader, who settled in present-day Chicago with his Potawatomi wife, Kitahawa, became increasingly acknowledged.

The controversy surrounding the naming of the school highlighted the complexities of racial identity and historical narratives. While some white residents opposed the decision, others within the Black community expressed a desire to retain the name of the existing Wendell Phillips High School, which had become a point of pride for many local families. Phillips, an abolitionist and advocate for Native American rights, had seen its demographics shift dramatically due to the Great Migration, where Black families moved to urban settings in search of better opportunities.

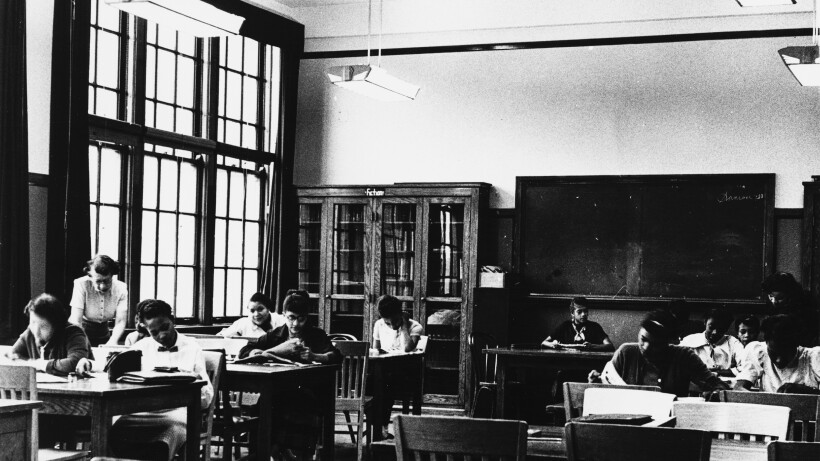

In the context of these changing demographics, the federal New Deal Public Works Administration provided funding for the construction of a new school that would eventually be named DuSable. The new facility opened in 1935 and was initially intended to serve as an extension of the existing Phillips High School. However, as student enrollment surged, it quickly transitioned into a high school with modern amenities, including laboratories, a library, and facilities for various trades.

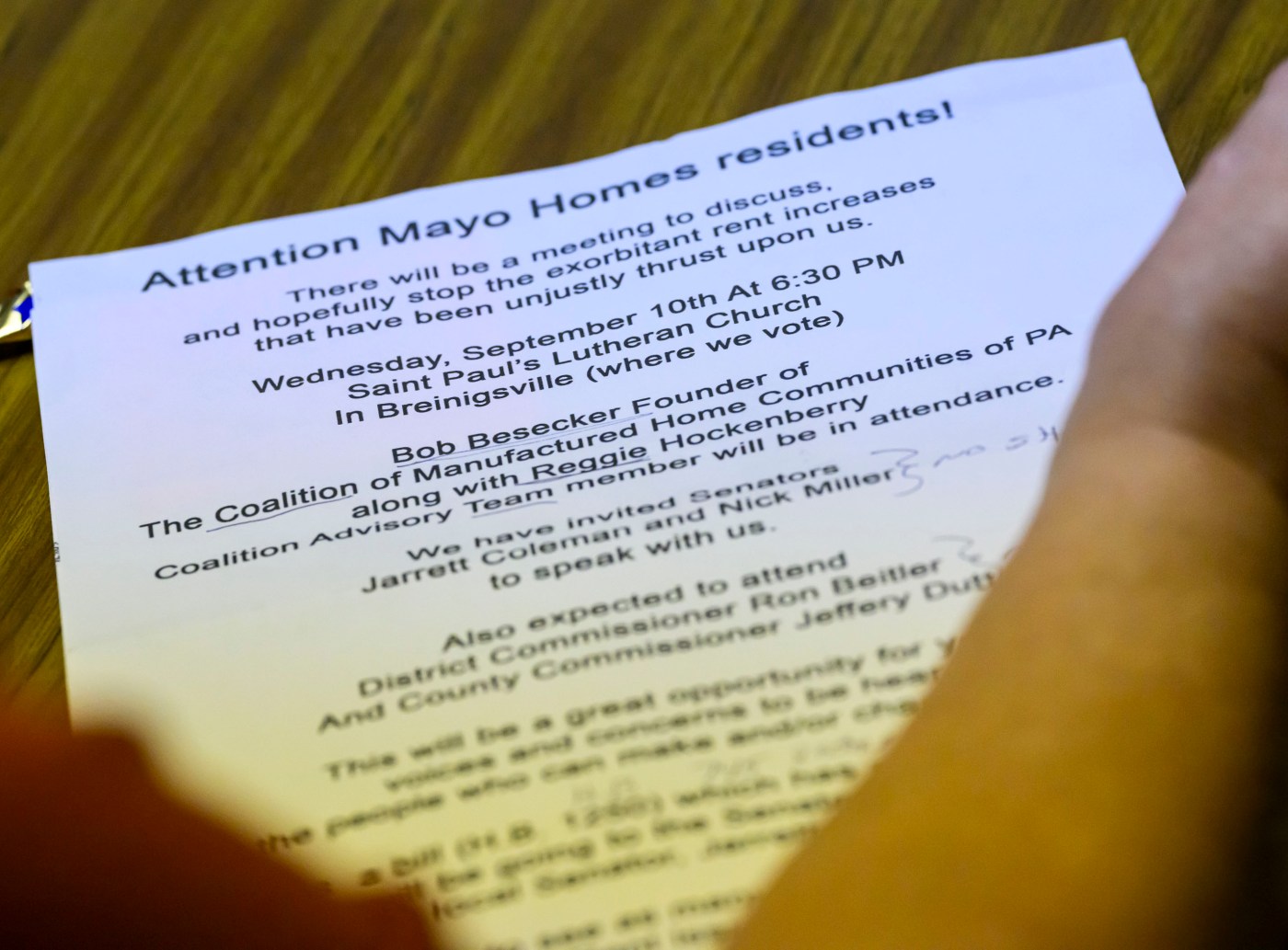

Advocacy for DuSable’s name came from groups such as the National De Saible Memorial Society, led by educator Annie Oliver. They sought to elevate the historical significance of Du Sable, opposing prevailing narratives that favored white settlers as the city’s original inhabitants. A June 1936 article in the New Journal and Guide documented the backlash against this name change, revealing the contentious nature of redefining Chicago’s history.

Despite some resistance from within the Black community, many recognized the importance of having a school built specifically for Black students. Todd-Breland emphasizes that DuSable High School represented a modern educational institution that aimed to provide equal facilities for Black students during a period of segregation.

For decades, DuSable earned a reputation for its robust arts program and diverse student body, peaking at approximately 4,000 students in the late 20th century. However, changing demographics and the closure of nearby public housing led to a significant decline in enrollment in the early 2000s. The school was subsequently reorganized into three smaller institutions, ultimately becoming a Chicago landmark in 2013.

The legacy of DuSable High School continues to resonate within the community. The DuSable Alumni Coalition for Action regularly hosts events to celebrate the school’s history and contributions to Black culture in Chicago. Recently, they honored Chief Justice P. Scott Neville Jr., a graduate of the class of 1966, underscoring the school’s ongoing influence on its students.

DuSable’s history is a testament to the resilience and cultural pride of the Black community in Chicago. Legendary figures such as Harold Washington, founder of Johnson Publishing John H. Johnson, and Don Cornelius, creator of “Soul Train,” walked its halls, shaping the city’s cultural landscape. The impact of educators like Captain Walter Dyett and Dr. Margaret Burroughs, who contributed to the creation of the DuSable Black History Museum, further solidifies the school’s legacy as a cornerstone of Black education and pride in Chicago.

As a vital institution for Black Chicagoans, DuSable High School exemplifies the ongoing struggle for educational equality and the celebration of African American heritage. Todd-Breland encapsulates this sentiment, stating, “This was such an important institution within Black Chicago… a place that folks really took pride in.”