The impact of MIT’s James Killian on Cold War defense strategies is profound, with roots tracing back to 1953. Just two months into Dwight Eisenhower‘s presidency, alarming intelligence revealed that the Soviet Union had detonated a nuclear bomb nine months earlier than anticipated. This unexpected development marked a significant shift in the balance of power, prompting an urgent reassessment of U.S. national security measures.

Eisenhower, who had previously led the Allies to victory in World War II, understood the complexities of global defense. His connections from his tenure as president at Columbia University became crucial as he sought to address the emerging Cold War threats. He advised his team to consult Killian, then president of MIT, to devise a comprehensive strategy.

Killian’s ascent to the presidency of MIT was unconventional; he was neither a scientist nor an engineer. According to David Mindell, a professor at MIT, “Killian turned out to be a truly gifted administrator.” His previous roles included serving as editor of the MIT Technology Review and overseeing the RadLab during World War II, which facilitated the development of crucial radar systems. Under Killian’s leadership, MIT launched the Lincoln Laboratory in 1951, a center dedicated to advancing air defense technologies.

In response to Eisenhower’s request in 1953, Killian quickly assembled a team of leading scientists to conduct a thorough evaluation of U.S. defense capabilities. This group formulated a three-part study to assess offensive capabilities, continental defense, and intelligence operations, which ultimately led to the creation of the Killian Report.

Delivering Strategic Insights

The Killian Report, submitted to Eisenhower on February 14, 1955, was a landmark document that would shape U.S. military and intelligence strategies for decades. The report detailed the need for a reassessment of U.S. vulnerabilities, emphasizing that while the U.S. held an offensive advantage in 1955, it remained susceptible to surprise attacks.

Killian anticipated that the geopolitical landscape would evolve into a dangerous phase where mutual destruction could occur if conflicts escalated. The report urged the U.S. to accelerate the development of intercontinental ballistic missiles and enhance cooperation with Canada for better intelligence-gathering efforts. Eisenhower, eager to integrate scientific perspectives into his decision-making, shared the report with heads of federal departments, igniting a competitive arms race between the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

While the Killian Report was grounded in current intelligence estimates, it also highlighted Eisenhower’s frustration with the limitations of the U.S. intelligence apparatus. Will Hitchcock, a history professor at the University of Virginia, noted that Eisenhower sought insights that could prevent surprise attacks similar to Pearl Harbor.

To tackle these intelligence challenges, Killian enlisted Edwin Land, co-founder of Polaroid and an innovative engineer with military experience. Despite their differing styles, Land quickly assessed the shortcomings within U.S. intelligence. He reported to Killian that interviews with military leaders left him concerned about the capability to answer critical questions about potential threats.

As the report progressed, Killian and Land briefed Eisenhower, proposing the development of missile-firing submarines and the U-2 high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft. These initiatives were pivotal in enhancing U.S. intelligence-gathering capabilities, though they later sparked complications in international relations.

Complex Legacy and Lasting Impact

The legacy of the Killian Report is intricate, marked by both advancements and unintended consequences. Christopher Capozzola, a history professor, highlighted the irony that Eisenhower aimed to mitigate interservice rivalries while inadvertently exacerbating them through the report’s recommendations. Furthermore, the report contributed to significant militarization of scientific research, a shift Eisenhower had initially warned against.

The most dramatic fallout occurred on May 1, 1960, when a U-2 aircraft was shot down over Soviet airspace just weeks before a pivotal meeting between Eisenhower and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. The incident shattered diplomatic efforts and complicated Eisenhower’s legacy as a peacemaker.

Despite these challenges, the Killian Report fundamentally transformed the relationship between the U.S. government and academic institutions, particularly MIT. It established a framework for collaboration that would direct research toward national interests, fostering a culture of scientific engagement in government affairs.

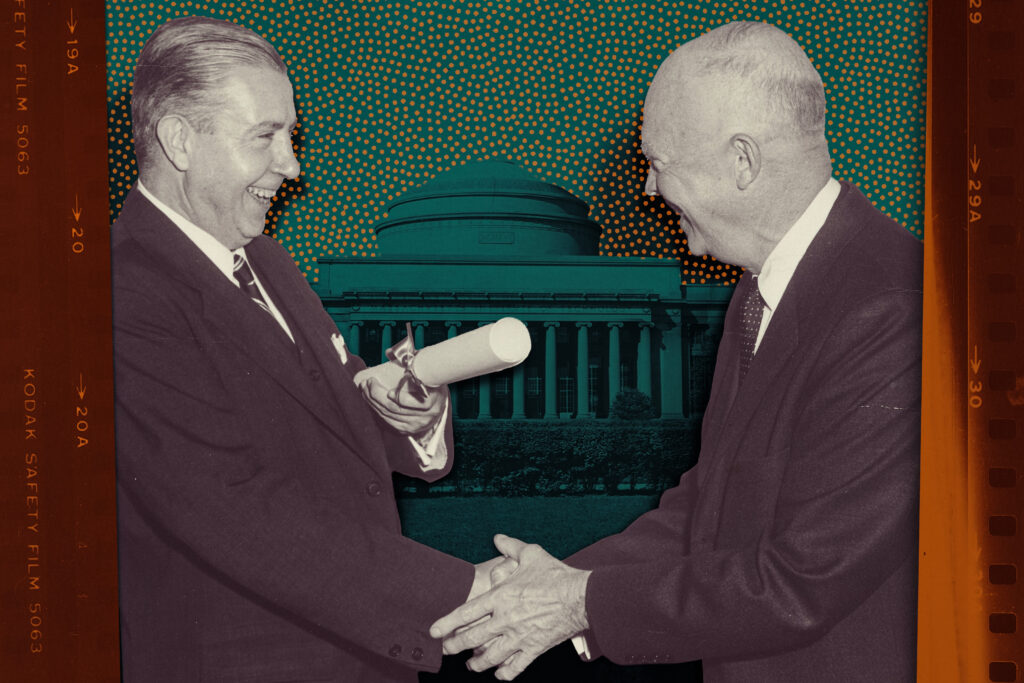

Killian’s influence extended beyond his presidency at MIT. Following the launch of Soviet satellite Sputnik, which alarmed the American public, Eisenhower appointed Killian as the first special assistant to the president for science and technology. In this role, he played a crucial part in shaping the national response to the space race, including the establishment of NASA.

Throughout his career, Killian maintained a close advisory relationship with Eisenhower, characterized by mutual respect and trust. His ability to navigate complex issues and offer sound advice positioned him as a vital figure in U.S. policy-making during a critical period in history.

In summary, James Killian’s contributions to Cold War defense strategies and the evolution of U.S. intelligence practices have had lasting impacts. His work not only shaped military technology but also influenced the broader relationship between science and government, setting a precedent for the involvement of research institutions in national security matters. Today, MIT continues to uphold this legacy, advancing knowledge in areas essential to national security and public welfare.