President Donald Trump has called upon Congress to implement a cap on credit card interest rates, proposing a limit of 10% during a recent address at the World Economic Forum in Davos. This initiative mirrors a legislative proposal already put forth by Senator Bernie Sanders. While this policy garners significant public support, it raises questions about its long-term implications for the economy, particularly for lower-income Americans.

Many Americans are currently feeling the financial strain from rising inflation and stagnant wages. However, the introduction of price controls on credit may exacerbate rather than alleviate these challenges. During his tenure as chief economist at the Office of Management and Budget, I witnessed firsthand how the previous administration’s economic strategies—rooted in free-market principles such as deregulation and competition—brought about substantial growth and lowered costs for consumers. The shift towards price controls now represents a departure from those foundational strategies.

The practical implications of a 10% cap on credit card interest could be severe. Currently, the average annual percentage rate (APR) for credit cards hovers around 20%, with significant discrepancies based on creditworthiness. Prime borrowers enjoy rates as low as 14%, while those with subprime credit histories face rates exceeding 25%. A cap at 10% would not eliminate default risks; rather, it would inhibit lenders from adequately pricing these risks, potentially leading to widespread credit restrictions.

According to the American Bankers Association, such a cap could result in at least 137 million cardholders losing access to credit cards. These individuals often rely on credit for emergencies, bridging gaps between paychecks, or building credit histories. With price controls in place, many could find themselves turning to high-cost alternatives, such as payday lenders or unregulated loan sharks, who may charge exorbitant rates.

Historically, similar measures have led to disastrous outcomes. For instance, interest rate caps in the 1970s severely curtailed consumer credit availability until a Supreme Court ruling allowed for interstate banking. In France, stringent usury laws have created a permanent underclass deprived of accessible credit. Japan’s experience in 2006 serves as another cautionary tale, as rate caps contributed to the collapse of the consumer finance industry, forcing many borrowers into the arms of organized crime.

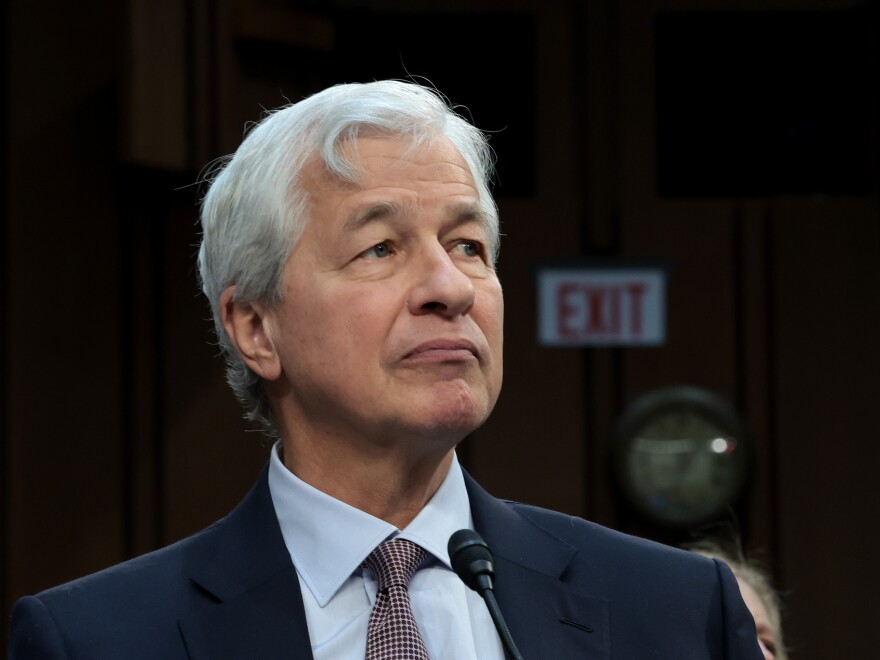

Critics of high credit card rates argue that these measures are necessary to curb excessive profits. However, credit card issuers typically operate on thin margins, as default rates consume much of the interest spread. For instance, JPMorgan Chase‘s credit card division recently reported a return on equity of 27%, a figure that, while healthy, reflects the genuine risks associated with lending.

The preferable approach lies in fostering competition and enhancing financial literacy among consumers. By eliminating regulatory barriers for new entrants, mandating clearer disclosure of terms, and encouraging alternatives like credit-builder loans and secured cards, access to credit can be expanded rather than restricted. The previous Trump administration recognized the importance of trusting markets, which ultimately proved effective.

Legislators promoting credit card rate caps are, in essence, battling fundamental economic principles. As with the laws of physics, economic laws remain unaffected by legislative efforts. The most vulnerable populations will feel the effects most acutely, discovering too late that a credit card with a 25% interest rate they can obtain is far more beneficial than a card capped at 10% that they cannot access.

In summary, while the intentions behind these proposals may be commendable, the consequences could lead to increased financial exclusion. A focus on market-driven solutions is essential for fostering economic growth and ensuring that individuals, particularly those in financial distress, have the opportunity to access credit responsibly.