Research conducted by scientists at the Institut Pasteur and Inserm reveals that common food emulsifiers can significantly impact the health of offspring. The study, published on December 26, 2025, highlights how the consumption of emulsifiers by mother mice alters their offspring’s gut microbiome from the earliest weeks of life. These alterations interfere with normal immune system development, leading to chronic inflammation and increased susceptibility to obesity and gastrointestinal disorders in adulthood.

Emulsifiers such as carboxymethyl cellulose (E466) and polysorbate 80 (E433) are prevalent in processed foods, enhancing texture and extending shelf life. They are commonly found in dairy products, baked goods, ice cream, and some powdered baby formulas. Despite their widespread use, the long-term health implications of these additives, especially concerning gut microbiota, remain underexplored.

Research Methodology and Findings

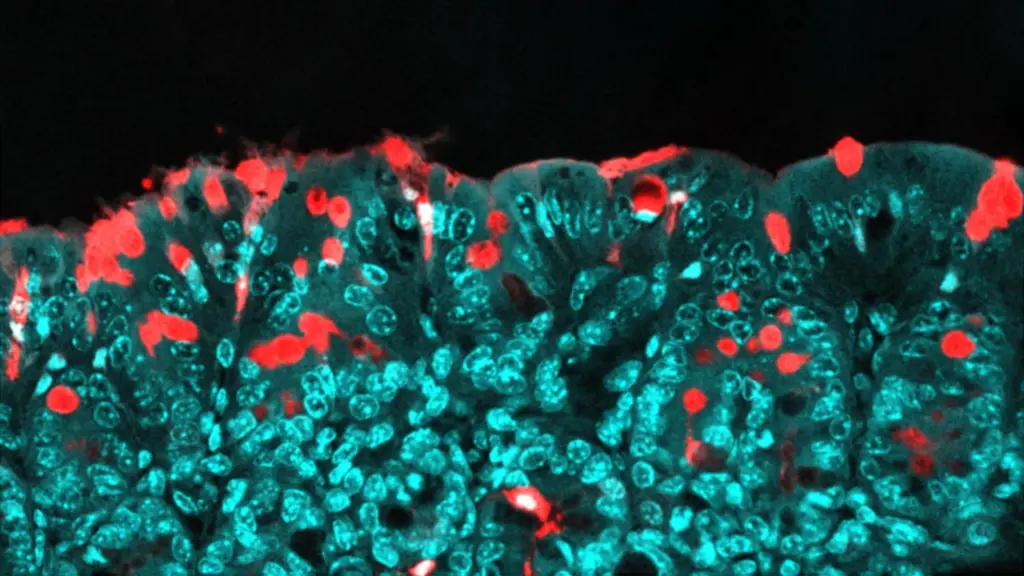

The research team, led by Benoit Chassaing, Head of the Microbiome-Host Interactions laboratory at Inserm, administered the emulsifiers to pregnant female mice from ten weeks before conception through lactation. The offspring, which had no direct exposure to these additives, exhibited significant changes in their gut microbiota during the crucial early weeks of life. This period is vital, as maternal microbiota can be transferred to offspring through close contact.

The study found that the young mice displayed an increase in flagellated bacteria, known for activating the immune system and promoting inflammation. Additionally, the researchers noted that the gut lining’s pathways closed prematurely, disrupting the necessary communication between gut bacteria and the immune system. This disruption ultimately led to an overactive immune response, resulting in chronic inflammation and an increased likelihood of developing inflammatory bowel diseases and obesity later in life.

Implications for Human Health

The implications of this research extend beyond mice, suggesting that similar effects may occur in humans. Chassaing emphasizes the necessity of understanding how dietary choices impact future generations. “These findings highlight the importance of regulating the use of food additives, particularly in powdered baby formulas, which are consumed during a critical phase for microbiota establishment,” he stated.

The study underscores the need for further research, particularly clinical trials examining mother-to-infant microbiota transmission. This research could explore the effects of maternal nutrition with and without food additives, as well as the direct exposure of infants to these substances in baby formulas.

The study received funding from the European Research Council through a Starting Grant and a Consolidator Grant, demonstrating a commitment to understanding the complex interactions between diet, microbiota, and health.

In conclusion, these findings from the Institut Pasteur and Inserm raise important questions about the long-term health effects of common food additives, urging policymakers and health professionals to consider stricter regulations surrounding their use, especially in products aimed at vulnerable populations such as infants.