A recent study reveals that the ancient settlement of Jiahu in China’s North China Plain not only survived the abrupt climatic disruption known as the 8.2 ka event, but also experienced significant social transformation during this period. Conducted by a team led by Dr. Yuchen Tan, the research challenges the notion that the event was uniformly catastrophic for all communities in the region. The findings are detailed in the journal Quaternary Environments and Humans.

The 8.2 ka event, which occurred approximately 8,200 years ago, was characterized by a sharp drop in temperatures and increased aridity across the Northern Hemisphere. Triggered by the collapse of the Laurentide ice sheet in North America, this climatic shift disrupted global weather patterns, including the East Asian Summer Monsoon. Areas like the North China Plain faced significant cooling and drought, leading many neighboring settlements to experience abandonment.

Located in Henan Province, the Jiahu site was occupied between 9,500 and 7,500 years ago. While many surrounding sites suffered disruption or were deserted, Jiahu demonstrated remarkable resilience. To analyze this phenomenon, the researchers applied resilience theory alongside the Baseline Resilience Indicator for Communities (BRIC) framework. This approach allowed them to assess how Jiahu adapted to the challenges posed by the climatic crisis.

Dr. Tan emphasized the importance of adapting the BRIC model, originally designed for modern communities, to evaluate how ancient societies reorganized in response to abrupt environmental changes. “Resilience is a universal concept,” Dr. Tan noted. “Even though ancient societies are very different from modern towns, they needed to reorganize, redistribute labor, strengthen cooperation, and adjust their use of resources when facing sudden change.”

The research examined three distinct phases of Jiahu’s occupation: Phase I (9,000 to 8,500 years ago), Phase II (8,500 to 8,000 years ago), and Phase III (8,000 to 7,500 years ago). The most significant transformations occurred during Phase II, coinciding with the 8.2 ka event. Burial records show a dramatic increase, with the number of burials rising from 88 in Phase I to 206 in Phase II. This surge likely reflects both increased mortality and an influx of immigrants from surrounding areas.

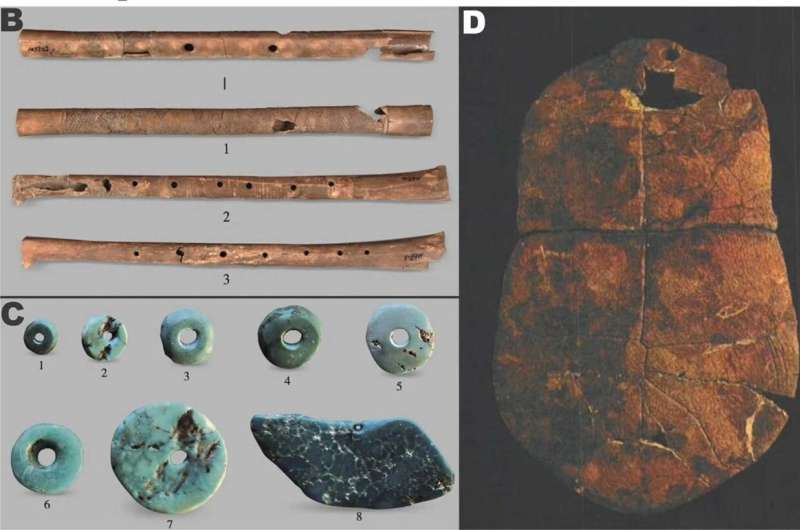

The study also revealed a shift in burial practices, with greater standardization and an increase in grave goods, which may indicate emerging social stratification. Analysis of skeletal remains pointed to a growing division of labor, as evidenced by higher rates of osteoarthritis in males, suggesting they engaged in more physically demanding activities.

As the population adapted, these changes likely enhanced Jiahu’s workforce capacity and efficiency, allowing the settlement to better secure food resources amid the challenges of the climatic event. By the time Phase III arrived, burials decreased to 182, and grave goods became less common, indicating a transformation in the community’s structure.

Dr. Tan explained that the ultimate decline of Jiahu did not occur until after Phase III, when the settlement faced frequent climatic fluctuations that resulted in flooding. “After Phase III, the Jiahu settlement faced frequent climatic fluctuations, which further triggered flooding and finally led to the decline of the Jiahu culture,” Dr. Tan stated. “Since the floods completely changed the structure of their habitat, the settlements were no longer functional when the floods hit.”

This research highlights the adaptive capacity of ancient communities during the 8.2 ka climate crisis. The application of the BRIC model to archaeological contexts offers a valuable framework for understanding how societies can reorganize in the face of abrupt environmental changes. The study underscores the importance of resilience in human history, demonstrating that even in the face of severe challenges, communities can innovate and transform.