A team of researchers from Case Western Reserve University has published a groundbreaking study on the ancient predator, Dunkleosteus terrelli, shedding new light on its anatomy and evolutionary significance. This study, featured in The Anatomical Record, marks the first comprehensive examination of this prehistoric fish in nearly a century, providing insights into its unique features and the role it played in its ecosystem during the Devonian period.

Dunkleosteus, which lived approximately 360 million years ago, was a formidable apex predator, reaching lengths of up to 14 feet. Unlike most fish, it possessed razor-sharp bony plates instead of teeth, which contributed to its reputation as one of the largest and most fearsome members of the arthrodire group. Since its discovery in the 1860s, it has fascinated both scientists and the public, with casts of its striking bony-plated skull displayed in museums worldwide.

A Long-Awaited Analysis

According to Russell Engelman, a graduate student in biology and lead author of the study, the last significant examination of Dunkleosteus’ jaw anatomy was published in 1932. At that time, the understanding of arthrodire anatomy was still in its infancy, focusing primarily on how the bones fit together. Engelman noted that modern advancements in paleontology, particularly from well-preserved fossils found in Australia, have dramatically improved knowledge of these ancient creatures.

The research team, which included experts from Australia, Russia, the United Kingdom, and Cleveland, utilized specimens from the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, home to the largest collection of Dunkleosteus fossils. The region’s geological conditions have preserved a wealth of skeletal remains, offering a rare glimpse into the life of this ancient fish.

Revelations About Dunkleosteus

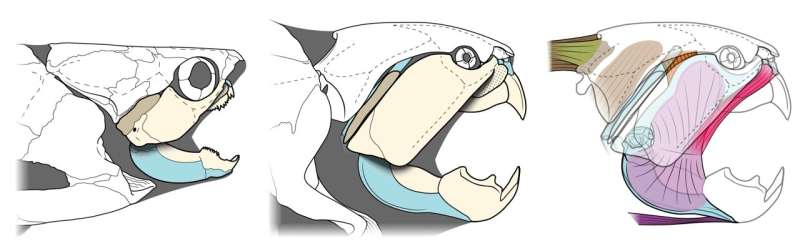

The study revealed several surprising findings regarding Dunkleosteus’ anatomy. Notably, nearly half of its skull was comprised of cartilage, including major jaw connections and muscle attachment sites, which contradicts previous assumptions about its skeletal structure. The researchers also identified a significant bony channel that housed facial jaw muscles similar to those found in modern sharks and rays, providing crucial insights into the feeding mechanics of ancient fishes.

Perhaps most intriguing is the research team’s conclusion that, despite being a hallmark representative of arthrodires, Dunkleosteus was an evolutionary oddity. Unlike its relatives, which possessed actual teeth, Dunkleosteus and its closest kin evolved to use their distinctive bony blades for hunting, adapting to prey on large fish.

Engelman emphasized the implications of these findings, stating, “These discoveries highlight that arthrodires cannot be thought of as primitive, homogeneous animals, but instead a highly diverse group of fishes that flourished and occupied many different ecological roles during their history.”

The research not only transforms the understanding of Dunkleosteus but also enriches the broader narrative of arthrodire diversity, suggesting that even the most renowned fossils can still offer new insights into ancient life.

For more detailed information, the full study is published in The Anatomical Record as of November 20, 2025, contributing significantly to the ongoing exploration of prehistoric marine ecosystems.